HTML and Word in mutt

I read my mail using mutt, and even though I was severely tempted by astroid, mutt just works too nicely for me to make moving away an attractive proposition. And it is a fine piece of software. If you're still stuck with Thunderbird (let alone some webmail interface in the browser) and wonder what text-based software you might adopt, right after vim I'd point you to mutt.

I'm saying all that because the other day I complained about a snooping mail marketing firm (in German) abusing MIME's multipart/alternative type to clickbait people reading plain text mails into their tracker-infested web pages, and I promised to give an account on how I configured my mutt to cope with HTML mails and similar calamities.

The basic mechanism is ~/.mutt/mailcap. That's a file analogous to /etc/mailcap, for which there's a man page, mailcap (5)[1]. That explains how, in general, software uses this file to figure out which program to use to display (or print or compose) files of which types.

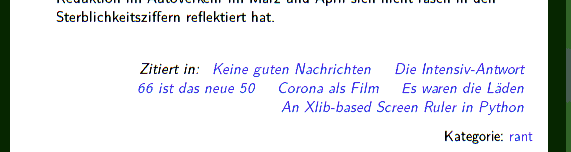

Mutt reads system-wide mailcaps, too, but I've found I generally want to handle a solid number of media differently in mails than, say, in browsers or from the shell[2], and hence I'm keeping most of this configuration in mutt's private mailcap. For HTML mail, I've put into that file:

text/html; w3m -dump -T %t -I utf-8 -cols 72 -o display_link_number=1 %s; copiousoutput

This uses w3m to format HTML rather than te lynx that the mutt docs give. Lynx these days really is too basic for my taste (I'm not even sure whether it has learned utf-8). Still, this will not execute javascript or retrieve images, so most of the ugly aspects of HTML mails are sidestepped. The copiousoutput option makes mutt use its standard pager when showing the program's output, and thus HTML mail will look almost like sane mail.

To make that really seamless, you need an extra setting in your ~/.mutt/muttrc:

auto_view text/html

This makes mutt automatically render HTML (which, contrary to the behaviour of gmail or thunderbird I consider relatively safe if it's parsimonious w3m that does the rendering). In addition, since I still believe in the good in humans, I believe that when there is both HTML and plain text in a mail, the plain text will be better suited for my text terminal, and so I tell mutt to prefer text/plain, which, again in the muttrc, translates into:

alternative_order text/plain

And that's it: If the villains at cleverreach (the marketing firm I complained about) didn't have their treacherous text/plain alternative, my w3m would render their snooping HTML without retrieving their tracking pixel and I could read whatever they send me without them ever knowng if and when. I'm still not sure if that's the reason they have the nasty clickbait text/plain alternative. In general, I support the principle that you should never explain with malice what you can just as well explain with stupidity. But then we're dealing with a marketing firm here…

Anyway: The best part of this setup is that you can quote-reply to HTML mails, giving your replies inline as $DEITY wanted e-mail to work. That is something that also is nice when folks send around MS office files (I get the impression that still happens quite a lot outside of my bubble). To cater for that, I have in my mailcap:

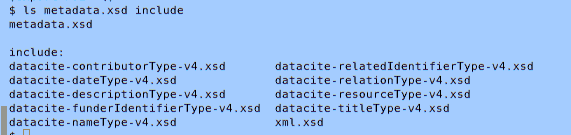

application/msword; antiword %s; copiousoutput application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document; docx2txt %s - ; copiousoutput

and consequently in the muttrc:

auto_view application/msword auto_view application/vnd.openxmlformats-officedocument.wordprocessingml.document

I admit I actually enjoy commenting inline when replying to office documents, and I trust antiword (though perhaps docx2txt a bit less) to not do too many funny things, so that I think I can run the risk of auto-rendering MS office files. I've not had to regret this for the, what, 15 years that I've been doing this for (in the antiword case; according to my git history, I've only given in to autorendering nasty docx in 2019).

I mention in passing that I have similar rules for libreoffice, but there I have a few lines of python to do the text rendering, and that is material for another post (also, folks decent enough to use libreoffice are usually decent enough to not send around office files, and hence auto-displaying ODT is much less of a use case).

Two more remarks: This actually cooperates nicely with rules not using copiousoutput. So, for instance, I also have in my mailcap:

text/html; x-www-browser file://%s

With that, if need by I can still navigate to an HTML file in the attachments menu and then fire up a “normal” browser (with all the privacy implications).

And: people indecent enough to mail around MS office files often are not even decent enough to configure their mail clients to produce proper media types. Therefore, mutt lets you edit these to sanity. Just hit v, go to the misdeclared attachment and then press ^E. Since the “Office Open XML“ (i.e., modern Microsoft Office) media types are so insanely long and unmemoralisable, I have made up a profane media type that I can quickly type and remember for that particular purpose:

application/x-shit; libreoffice %s

| [1] | In case you're not so at home in Unix, writing “mailcap (5)” means you should type man 5 mailcap (for “show me the man page for mailcap in the man section 5”) to read or skim the documentation on that particular thing. Explicitly specifying a section has a lot of sense for things like getopt (which exists in sections 1 and 3) and otherwise is just an indication that folks ought to have a look at the man page. |

| [2] | You can use programs like see (1) or even compose (1) to use the information in your non-mutt mailcaps. |

![[RSS]](../theme/image/rss.png)